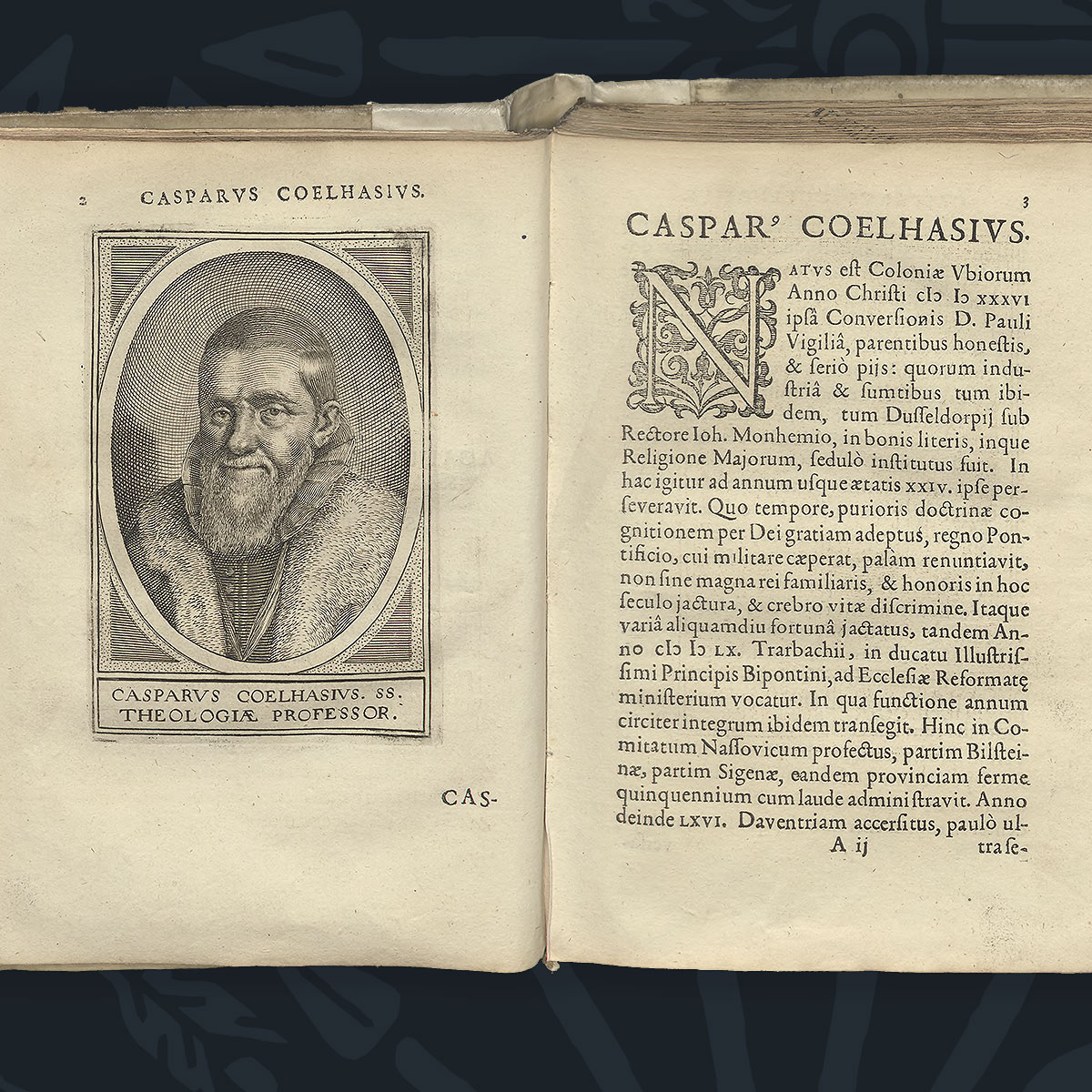

Caspar Coolhaes (1536–1615): A Life in the Crossfire of the Dutch Reformation

Caspar Coolhaes (1536–1615) lived through one of the most turbulent eras in European history: the Reformation and the rise of Protestantism. Protestantism was a movement that emerged in the 16th century as a response to perceived corruption within the Catholic Church, leading to a split that would forever change the religious and political landscape of Europe. At its core, Protestantism rejected the authority of the Pope, emphasized the primacy of Scripture, and called for a return to what reformers saw as the original teachings of Christianity.

By the mid-late 16th century, Protestantism had splintered into two primary branches: Lutheranism and Calvinism. Lutheranism, based on the teachings of Martin Luther, emphasized salvation by faith alone and the idea that grace could not be earned through good works. Calvinism, following the teachings of John Calvin, introduced the doctrine of predestination—the belief that God had already determined who would be saved and who would be damned. Calvinists also emphasized the sovereignty of God in all matters of salvation and governance. It was within this Reformed tradition, and its dominance in the Dutch Republic, that Coolhaes would make his mark.

Coolhaes emerged as a key figure in the theological debates of the late 16th century, particularly within the Reformed Church. His career was defined by his resistance to the strict Calvinist doctrines of his time, especially predestination, and his advocacy for religious tolerance. In a period when the Reformed Church in the Dutch Republic was consolidating its influence, Coolhaes’ ideas were considered radical, placing him in direct conflict with the more orthodox elements of Calvinist leadership.

Early Life and the Beginnings of a Career

Coolhaes was born in 1536 in the city of Cologne, a major center of commerce and Catholicism within the Holy Roman Empire. Educated at several universities, he became exposed to the theological ideas that were transforming Europe in the wake of the Protestant Reformation. By the time he was ordained as a minister, the Reformation had already taken root in many regions, and the newly emerging Protestant movements—especially Lutheranism and Calvinism—were rapidly gaining adherents.

In 1570, Coolhaes was appointed as a minister in the city of Leiden, a stronghold of Calvinism in the Dutch Republic. The Reformed Church, led by Calvinists, was attempting to establish itself as the dominant religious authority in the region. But Coolhaes envisioned a more open and tolerant form of Protestantism, challenging the rigid doctrines that were beginning to characterize the Reformed movement. This would set him on a path of theological conflict and controversy.

A Radical Advocate of Religious Tolerance

Caspar Coolhaes’ career took a dramatic turn when he began advocating for greater religious tolerance. He argued that Reformed Protestantism should not become as dogmatic and exclusive as the Catholic Church it had replaced. His views were shaped by a broader theological movement of “libertine” thought that emerged during the Reformation, particularly within the Reformed tradition.

In the context of the 16th century, the term “libertine” referred to those who opposed strict religious and moral constraints. Libertine theologians within the Reformed movement emphasized personal freedom in matters of faith, resisting the institutionalized dogma they saw solidifying within the Calvinist hierarchy. These theologians were particularly critical of the doctrine of predestination. For libertines like Coolhaes, this idea—that God had preordained who would be saved—was spiritually suffocating and fundamentally unjust.

Coolhaes argued that the state should allow for religious plurality, and that faith should be a matter of personal conviction, not forced compliance with a monolithic Calvinist orthodoxy. His vision was one in which Protestants of different theological views—Calvinists, Lutherans, Anabaptists, and others—could coexist peacefully. But in the context of the Dutch Republic, where Calvinism was intertwined with the political struggle against Catholic Spain, these ideas were seen as dangerous.

The Controversy Over Predestination

At the core of Coolhaes’ theological dissent was his rejection of predestination, a key doctrine of Calvinism. According to Calvinist theology, salvation was not earned through faith or works; it was preordained by God, who had chosen the “elect” for salvation and destined others for damnation. For Coolhaes, this doctrine was not only spiritually troubling but also politically divisive, as it reinforced an exclusivist religious identity that could alienate large segments of the population.

Coolhaes was not alone in his opposition to predestination. Throughout Europe, a significant minority of Reformed thinkers—often drawing from the humanist traditions of figures like Desiderius Erasmus—argued for a more inclusive understanding of salvation. This was a broader tension within the Reformed movement itself, between those who advocated for strict orthodoxy and those who sought to embrace a more spiritual, individual relationship with God.

Related to this debate was the concept of “spiritualism,” a theological position that emphasized the internal, personal aspects of faith over external rituals or rigid doctrines. Spiritualists believed that Christianity was ultimately about the inner transformation of the believer, not the imposition of institutional control. Coolhaes, while not strictly a spiritualist, shared many of their convictions, especially in his insistence that faith must be grounded in individual conscience rather than collective enforcement of predestination.

Conflict with the Reformed Church

The Reformed authorities in the Dutch Republic were unwilling to tolerate Coolhaes’ dissent. In 1578, his views on religious tolerance and his criticism of predestination led to a formal investigation by the Synod of Dordrecht. The synod found him guilty of undermining the unity of the Reformed Church and promoting heterodox ideas. As a result, Coolhaes was dismissed from his position as minister in Leiden and largely silenced within the official Reformed Church.

He opened a brewery in the city and continued to write and debate, though now as an outsider. His ideas about religious tolerance and the dangers of predestination found a small but important audience among Protestants who resisted the increasingly rigid Calvinism of the Dutch Republic, including the famous (or notorious?) Jacob Arminius, who was a student at Leiden while Coolhaes was a professor. His writings circulated within Arminus’ circles and those who continued vis-a-vis his eponymous movement, informing and influencing a theological response to the rigid Calvinist orthodoxy that would come to prominence in the early 17th century in the wake of the Synod of Dort.

The Broader Context: Religious Divides in the Late 1500s

The conflicts that surrounded Caspar Coolhaes were part of a larger story about the divisions within Protestantism in the late 16th century. While Protestantism had begun as a united front against Catholicism, it had by this time fractured into competing sects, each with their own distinct doctrines and practices. Calvinism, which had taken hold in the Dutch Republic, sought to establish itself as the dominant religious force, backed by both political leaders and church authorities. Lutheranism, while influential, was more prominent in Germanic and Scandinavian regions.

In the Dutch Republic, the Reformed Church was closely tied to the political and military struggle against Spanish rule. Calvinist leaders saw religious orthodoxy as essential to maintaining the moral and political cohesion of the newly independent Dutch state. Coolhaes’ calls for religious tolerance and his rejection of Calvinist predestination placed him in opposition not only to the Reformed Church but to the political leadership of the Dutch Republic, who feared that religious pluralism could weaken their cause.

Coolhaes’ Legacy

Caspar Coolhaes died in 1615, largely forgotten by the Reformed Church that had cast him out, but remembered by a small group of thinkers who continued to advocate for religious tolerance. His ideas about the dangers of predestination and the need for a more inclusive Protestantism would resurface in the Arminian controversy, which shook the Dutch Republic in the years following his death.

Today, Coolhaes stands as a reminder that the Reformation was not a monolithic movement. It was a period of intense theological debate and experimentation, in which figures like Coolhaes struggled to balance the demands of religious purity with the need for tolerance and inclusivity. His story offers a valuable perspective on the tensions within the Reformed tradition and the broader Protestant world during the late 16th century.

For those interested in exploring the life and thought of Caspar Coolhaes further, his works offer a window into the rich and often contentious world of Reformed Protestantism. His legacy continues to resonate in discussions of religious tolerance and the limits of orthodoxy.

For More:

Gottschalk, Linda Stuckrath, Pleading for diversity : the church Caspar Coolhaes wanted (https://scholarlypublications.universiteitleiden.nl/handle/1887/38762)

J. Wayne Baker, Review of Ulrich Gäbler, “The spread of Zwinglianism into the Netherlands and the Downfall of Caspar Coolhaes 1581/1582,” The Sixteenth Century Journal, 17 (1986)