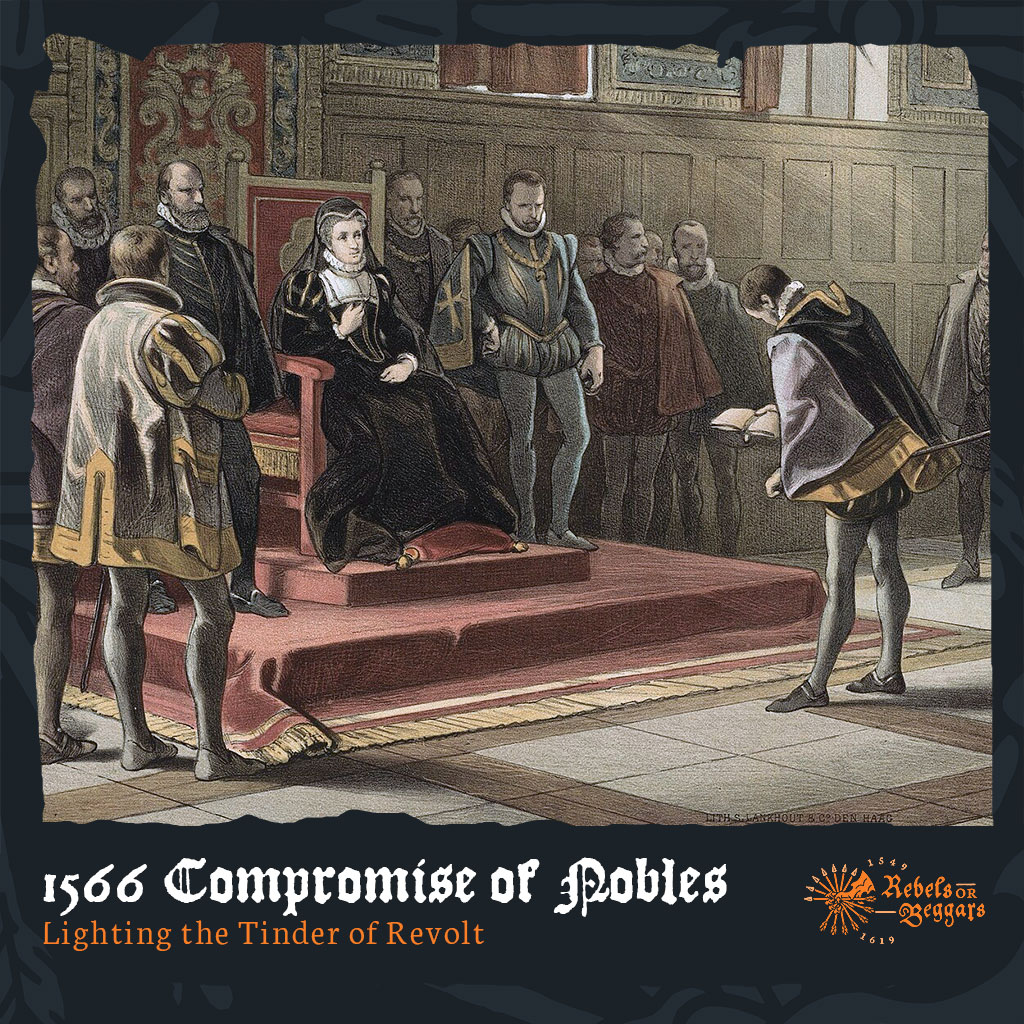

The 1566 Compromise of Nobles: Lighting the Tinder of Revolt

In 1566, Dutch nobles demanded tolerance from Spain, but an insult gave birth to a rebellion. Here's how the Geuzen were born from a royal dismissal.

The spring of 1566 found Brussels tense and uneasy.

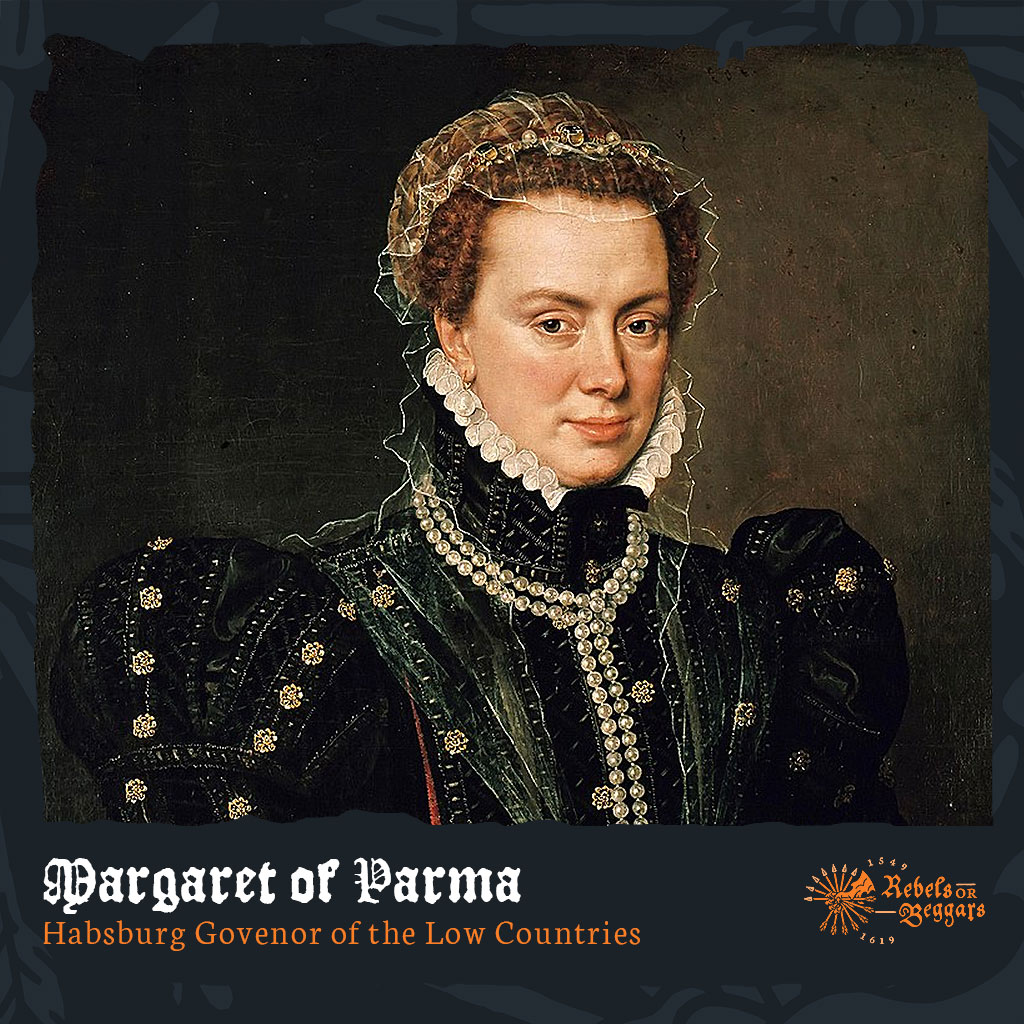

Margaret of Parma, the Spanish king’s half-sister and regent in the Low Countries, found the court at Coudenberg Palace caught in a tightening vise: economic malaise, religious unrest, and persistent suspicion that Philip II – her half-brother as well as the Hapsburg king in far-away Madrid – did not grasp the severity of the situation.

So when more than two hundred nobles on horseback, armed with swords, and marching in solemn procession arrived at her court on 5 April, their appearance was as much theater as it was protest. Clad in muted colors and united under a shared petition, they marched deliberately past guards and courtiers, carrying their grievance to the very heart of Habsburg authority.

At the center of their appeal was a document that would soon echo across Europe: the Compromise of Nobles. In it, the signatories demanded a halt to the Inquisition and the harsh religious edicts imposed by Philip II. Their goal, at least publicly, was moderation—not rebellion. Yet the spectacle of so many lesser lords presenting a coordinated political challenge alarmed the court.

Charles de Berlaymont, the Grand Huntsman of Brabant and one of Margaret’s closest counselors, tried to reassure the regent, saying, “Fear not, Madame, they are only beggars.”

It was meant to dismiss them. But the nobles seized the insult and wore it with pride. From that moment forward, the Geuzen—the Beggars—had a name.

Today, Queen Elizabeth is remembered for standing tall against the Spanish Armada. But years before that climactic moment, a very different storm was brewing across the Channel in the Low Countries. Spain ruled these territories, but it was a rule increasingly challenged by religious change, rising taxes, and local autonomy.

This article explores the dramatic moment in April 1566 when a group of Dutch nobles, known as the “Compromise of Nobles,” demanded religious tolerance from Spain—and how a single insult sparked a movement that reshaped the Netherlands for generations.

Dissent Under a Spanish Crown

When Philip II inherited the Low Countries from his father Charles V, he also inherited a delicate balance. The seventeen provinces were wealthy, fractious, and deeply tied to local rights and privileges known as “liberties.” But Philip’s goal was unambiguous: defend Catholicism, centralize power, and impose a uniform system of governance.

In the 1550s and 1560s, the provinces were roiled by the spread of Calvinism and the harsh enforcement of anti-heresy laws. The Inquisition was active, and thousands were executed for their beliefs. At the same time, Philip’s absence—he ruled from Madrid—and the reliance on foreign advisors like Cardinal Granvelle alienated even loyal Catholic nobles.

The final straw was the plan to increase the number of bishoprics and further empower the Inquisition. Many nobles felt their authority and privileges were under direct threat.

Why it matters: This environment of fear, repression, and alienation gave rise to the Compromise of Nobles as a desperate plea for religious tolerance and local autonomy.

The Petition and the “Compromise”

By early 1566, a group of about 400 nobles from across the Netherlands had organized a formal appeal to Margaret of Parma, the half-sister of Philip II and his regent governor of the Low Countries (then united as the Seventeen Provinces).

They called themselves the “Confederated Nobles” and on 5 April 1566, a group of 200-300 of these noblemen – all armed with swords as permitted by their station – presented a document known as the “Compromise” to Margaret and his councillers.

The document urged Margaret to suspend the enforcement of heresy laws, warning that continued persecution would provoke rebellion. The nobles maintained loyalty to the king but called for moderation and reform.

Their leader, Hendrik van Brederode, delivered the petition with style and urgency. Though Margaret was unsettled, she remained calm. But her advisor, Charles de Berlaymont, reportedly tried to calm her with a phrase that would echo for decades: “N’ayez pas peur, Madame, ce ne sont que des gueux”—“Do not be afraid, madam, they are only beggars.”

The key takeaway: The term “Geuzen” (beggars) began as an insult but quickly became a badge of honor.

From Insult to Emblem

That next day, 6 April 1566, the nobles gathered for a celebratory banquet in Brussels townhome of Floris I van Pallandt, Count of Culemborg.

Inspired by the slur, they embraced the insult. Wine flowed freely, and the air was electric with rebellion. Nobles donned grey cloaks like beggars and pledged loyalty to the king—even if it meant wearing the beggar’s pouch.

They created a new motto: Fidèle au roy, jusqu’à porter la besace—“Loyal to the King, even to carrying the beggar’s pouch.” The medallion of a beggar’s bowl and spoon, slung around the neck, became a rebel badge. From this moment forward, “Geuzen” would refer to those resisting Spanish rule, first in symbol and soon on the battlefield.

Why it matters: The nobles’ theatrical defiance turned a dismissive insult into a revolutionary identity that would define Dutch resistance for decades.

Who Were the Compromisers?

Though many men signed the petition, a handful stand out as leaders and symbols of the movement.

Louis of Nassau, younger brother to William of Orange, was a Calvinist firebrand and key organizer. He played an essential role in uniting the nobles across provincial lines and rallying support from Huguenot and Protestant allies abroad.

Hendrik van Brederode, a charismatic Catholic nobleman with a flair for drama, was the face of the movement. His speech and toast at the Culemborg banquet cemented the Geuzen identity. He would later attempt to raise an army and continue the resistance, though with limited success.

Floris I van Pallandt, Count of Culemborg, played a key supporting role in the early stages of the Compromise. Though less politically prominent than figures like Brederode or Louis of Nassau, Floris provided a crucial venue for protest: it was in his Brussels townhouse where nobles feasted, drank, and first embraced the name “Geuzen.” A moderate Catholic sympathetic to reform, his quiet involvement reflected the broad range of opinions and alliances within the rebel cause.

Philippe de Marnix, Lord of Saint-Aldegonde, a gifted writer and polemicist, provided the movement with its ideological edge. Though not present at the April 5 presentation, he would become one of the revolt’s intellectual architects.

Why they’re important: These men gave the Compromise both a public face and long-term momentum, blending political theater with genuine reformist intent.

The Aftermath and Legacy

Margaret of Parma, shocked by the number and rank of petitioners, agreed to suspend persecution temporarily—a tactical delay that bought time. But as Calvinist preachers began holding outdoor sermons with thousands of followers, tensions escalated quickly.

By August 1566, the Iconoclastic Fury (Beeldenstorm) broke out. Protestant mobs attacked churches, destroying Catholic imagery in a wave of righteous zeal. Margaret’s fragile peace collapsed. Philip II dispatched the Duke of Alba with an army in 1567, ushering in an era of repression that would ignite full-scale revolt.

But the Geuzen identity endured. Over the next two decades, “Sea Beggars” harassed Spanish shipping, and rebel forces marched under Geuzen flags. Even as leadership passed to William of Orange, the symbolic power of the 1566 moment remained foundational.

The key takeaway: The Compromise of Nobles was more than a petition; it was the spark that transformed political dissent into national rebellion.

Epilogue in Symbols and Memory

Long after the events of 1566, the symbols of the Geuzen retained power. In the Eighty Years’ War that followed, Geuzen emblems appeared on banners and coins. The phrase “Fidèle au roy, jusqu’à porter la besace” became ironic as many Geuzen turned against the king entirely.

In later centuries, the Geuzen would be remembered as heroes of Dutch independence, though their origins were more complex. They began as moderate nobles seeking religious tolerance, not revolution. Yet they lit the flame that burned through nearly a century of war.

Why it matters: Understanding the birth of the Geuzen helps us see how symbols, slurs, and spectacles can shape revolutions and national identities.

History turns on moments like these—not always dramatic battles, but quiet insults, public theater, and collective defiance. What are the moments in history you feel are overlooked but deeply transformative?

For further reading on the origins of the Dutch Revolt and the cultural and political currents of the sixteenth-century Low Countries, I recommend The Dutch Revolt, by Geoffrey Parker. Though published by Penguin Books in 1977, Prof. Parker’s work remains a seminal study on the conflict.