Platin Printer’s Device Tattoo

The life of Flemish printer Christophe Plantin (c. 1520–1589) has long been a curiosity and inspiration to me.

He was a master of navigating a a society unraveling at its very seams: the escalating, bellicose rhetoric of both the traditionalist, reactionary Roman Catholics and their enemies: the we’re-not-going-to-take-it reformist Calvinists.

People were to take sides. Anyone in the middle, anyone mediating religious peace and civility was accosted by the partisans and true believers in both Catholic and Calvinist camps.

Insults and incendiary propaganda turned to assaults and violence in the streets. Executions at the hands of the Catholic Inquisition was met in vulgar kind by the lynching and murder of Catholic priests and monastics.

The violence became gasoline thrown on the embers of civil unrest and rebellion, exploding into all-out war.

(I sadly admit that one of the reasons I’m so fascinated by the Dutch Revolt may be because I see the echoes of its tensions and conflicts here in the twenty-first century United States.)

Which brings us back to Christophe Plantin.

As one of the most renowned printers of the 16th century, he built a thriving business in Antwerp, serving powerful clients like Spain’s Catholic King Philip II. His Polyglot Bible, commissioned by the crown, stands as a monumental achievement. Yet beneath the surface, Plantin played a far more dangerous game, secretly publishing works for Protestant sects defying the very monarchy that paid him.

His life grew even more complex with his involvement in the clandestine Family of Love, a radical sect that rejected institutionalized religion in favor of a mystical, spiritual faith. Balancing on a razor’s edge between royal favor and subversion, Plantin’s career was defined by secrecy, ingenuity, and his ability to navigate the treacherous waters of the Reformation.

The Tattoo

I am slowly working on finishing a patchwork-like sleeve of tattoos, all in blackwork and mostly in old school, traditional Americana style. But with some space at the end of my arm, I wanted something reflecting my love of history in an etching or engraving style.

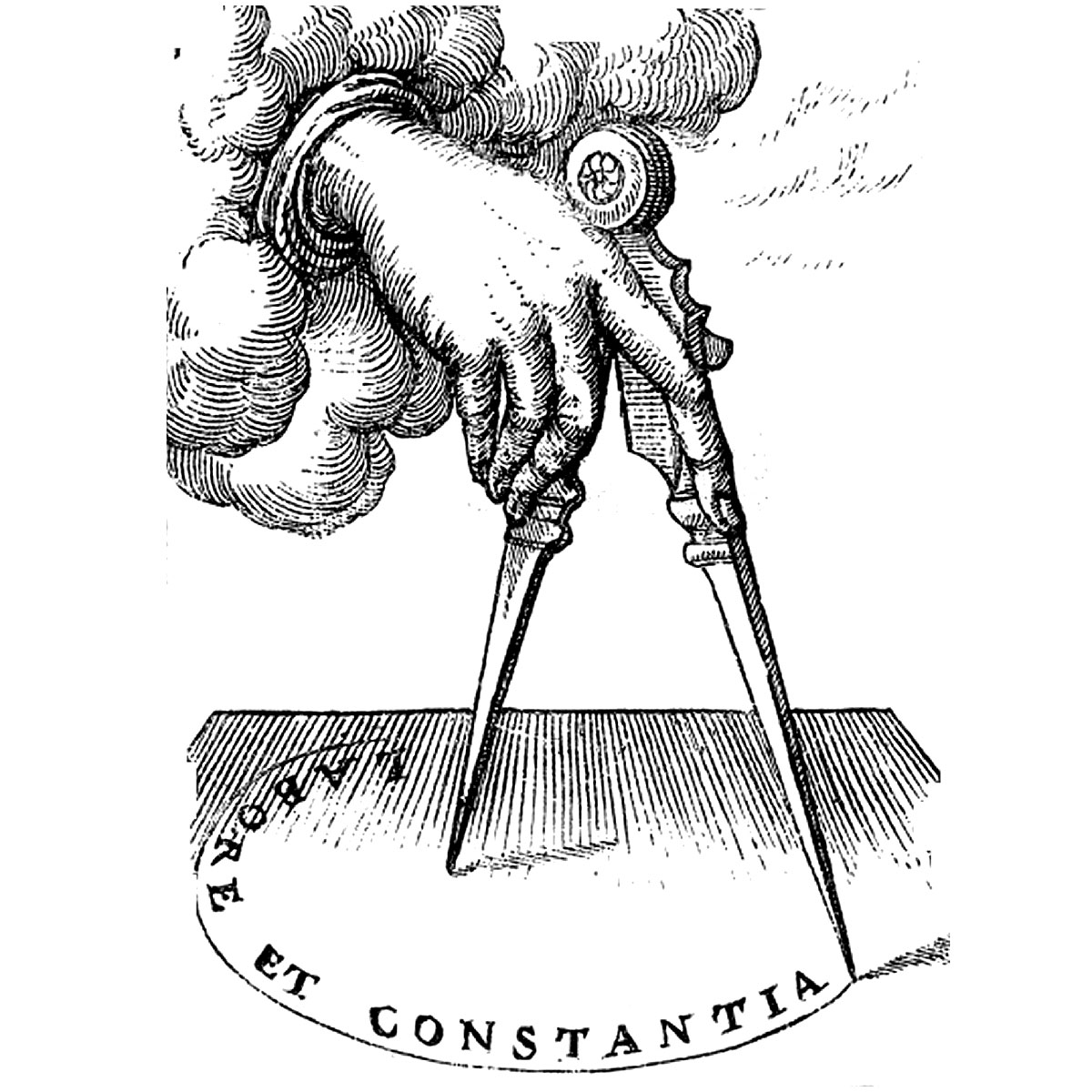

Thus Platin’s printer’s mark: the hand upon the compass.

(Printer’s marks – also printer’s devices – were early trademarks: each printer would have his own design, usually a symbolic device with a motto or initials.)

Platin always paired the compass with the Latin motto Labore et Constantia (Labor and Constancy), usually a background treatment, and both text and design placed within a frame of some sort.

However, with the shape and size of the space available on my arm, my artist and I decided to focus on just the hand emerging from the clouds with the compass.

The work was done by Chris Boyle at Promised Land Tattoo in St. Louis.

I’m pleased with the piece, as you’d imagine, both as an homage to my love of history, but also as commentary to the tumultuous political times those of us in the United States have found ourselves in the past several years.

It’s a reminder to myself: beware the extremes and find a way to navigate between them.

Christophe Platin Printer’s Devices

For reference, here are a collection of Christophe Plantin’s printers devices I sent to my tattoo artist Christ for reference: