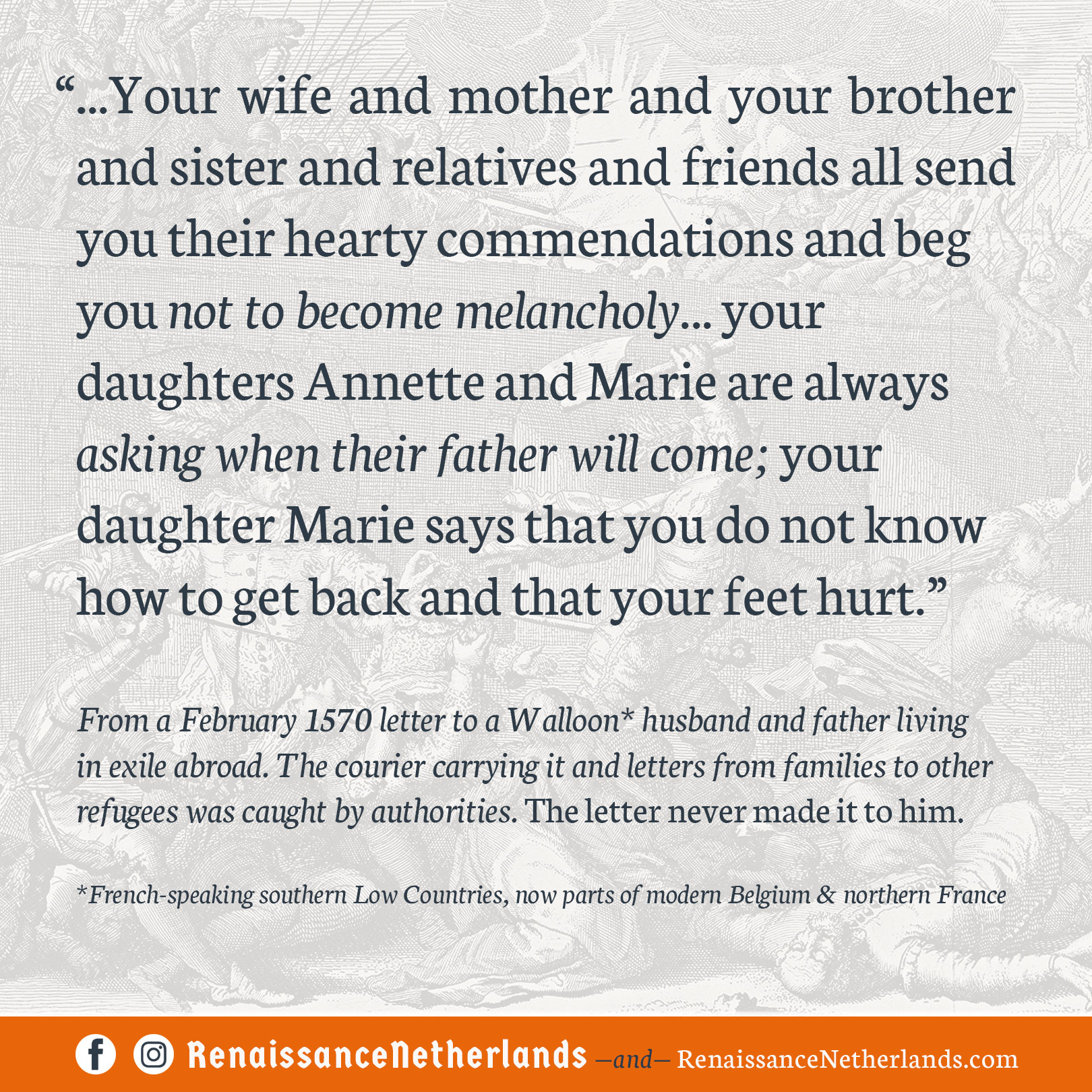

1570 Letter to an Exiled Walloon Father and Husband

An example of the human experience from history.

These were people like you and I.

The years following Philip II’s ascension to the throne of a united Spain and the Seventeen Provinces of the Low Countries saw a dramatic rise in tension across all layers of society.

Confrontations with the Habsburg government grow more frequent while religious agitation by both Reformed Protestants and Roman Catholics grew in fervor. By 1566-1567, dissent had grown into rebellion and revolt.

Philip II ordered the “Iron Duke” of Alva to the Low Countries to restore order. His draconian efforts temporarily succeeded in quelling the rebellion, but at a high cost. His “council of blood” summoned more than ten thousand and lead to the deaths of a great many – both humble city folk and powerful nobles.

Many fled rather than submit themselves to a nearly-certain execution. By 1570, England and the neighboring cities and towns of the Rhine river region, Westphalia, and Huguenot-controlled France were common centers for the tens of thousands of Dutch and Flemish refugees.

Often, families were separated. Wives and children and parents left behind. Worldly goods, mementos, and valuables left behind – and often confiscated – in a frantic flight to more tolerant places.

A network of clandestine couriers developed to keep separated friends and families in touch.

Here we see an example of concerns that we see in our modern selves when writing – or Facetiming! – family members separated by many miles and a global pandemic.

Dated 1 February 1570, to a Walloon husband and father who had taken refuge in Calais. Writing by a friend on behalf of his wife and family:

“May the grace and peace of our good God be granted to you as a greeting.

Martin, be informed that your wife has received your letter, dated 27 December, by which she was very happy when she heard of your good state.

Note, that your wife and mother and your brother and sister and relatives and friends all send you their hearty commendations and beg you not to become melancholy, for, at the moment, no one is saying anything [about you?] in Valenciennes. You have heard tell that they are confiscating the goods of people; it is very true that they have confiscated the goods of some of those who are banished or accused, but, they are not saying anything for the moment.

And I wish that you were with your wife and children, for you would be at ease as much as the others who return every day. You ask me to see if the roads are dangerous, but concerning that you will have to have patience, for I hope, depending on the grace of God, that he will change matters and that you will return by his grace, for it is hardly a journey for a woman and two children. For which reason, place your confidence in God and with time you will come a little nearer in time.

Note that the wife of Boisin has given birth to a son.

I have nothing else to tell you for the moment, except that your daughters Annette and Marie are always asking when their father will come; your daughter Marie says that you do not know how to get back and that your feet hurt.

May you be commended to God.From Valenciennes, this first day of the month of February in ’69.

Martin, inquire a bit to discover where Martin du Val is, for his father and mother wish very much to hear his news. To end, by Jesus Christ.”

This letter was never delivered to Martin Plennart. The courier, Henri Fléel, was captured in a small boat, where his cargo of illicit letters was discovered in a hidden compartment.

Poor Henri was sentenced as a “obstinate heretic” and likely executed. The letters were confiscated by the Council, where they remained in storage until uncovered by a Belgian scholar centuries later.

Selected Sources

Letters from families and contacts in Wallonia and Flanders to their Protestant relatives and acquaintances in south-east England, 11 November 1569 -25 February 1570

https://dutchrevolt.leiden.edu/english/sources/Pages/Verheyden-Correspondence.aspx

Susan Broomhall, “Cross-Channel Affections: Pressure and persuasion in letters to Calvinist refugees in England, 1569–1570” in Feeling Exclusion: Religious Conflict, Exile and Emotions in Early Modern Europe

https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429354335

Geert H. Janssen, “Exiles and the Politics of Reintegration in the Dutch Revolt” in History, Vol. 94, No. 1

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24428519